NY is weighing weapons detectors on its subways, but there are questio

This article was published in partnership with New York Focus, a nonprofit newsroom covering state and local politics in the Empire State. Sign up for their newsletter here.

Last month, the day after a gunman opened fire on a crowded Brooklyn subway, New York City Mayor Eric Adams went on Good Morning America to talk about his plans for improving transit security. His big idea, which he had first floated in January, involved installing artificial intelligence-driven weapons detectors in the subway system.

“Technology has advanced so much,” Adams said. “There’s a new method that can detect weapons that are not the traditional metal detectors that you see at airports. You don’t even realize it’s there.”

But the technology Adams was talking about, which has never been implemented at scale on public transit, has issues that could present major problems for New York’s more than 3 million daily pandemic-era subway passengers. The detectors can be inaccurate, misidentifying an array of everyday objects, from cell phones to umbrellas, as threats. When those detectors ping an item, the person carrying it must be routed to more conventional secondary screening, which could cause significant delays for riders.

Even some companies that sell the technology that Adams is proposing — which is currently deployed in schools, workplaces, hospitals, and ticketed venues across the country — aren’t sure that it’s ready for public transit. Speaking to security and surveillance tech research firm IPVM late last month, Peter Evans, CEO of Patriot One Technologies, which sells its covert walk-through weapons detectors to event venues and secure buildings, said it would “radically change” subway riders’ experience. “Expect delays, expect secondary screening, expect frustration and expect to miss your train from time to time,” he said.

Albert Fox Cahn, executive director of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project, agreed. “If we actually tried to deploy this technology, it would be absolute chaos at the train stations,” he said. “They clearly aren’t ready for primetime.”

While the Adams administration is still working out the details of its official proposal for subway scanners, it has confirmed one vendor on its shortlist: Massachusetts-based Evolv Technology, whose products and business model illustrate the potential pitfalls of deploying weapons detectors in mass public transit systems. (Evolv is confident in its systems’ utility, with CEO Peter George telling The Wall Street Journal after the Brooklyn shooting that his company was “born to solve this exact problem.”)

Like its competitors’ products, Evolv’s systems involve walk-through full body scanners equipped with machine learning software programmed to distinguish guns, knives, and other “threat” objects from everyday items. In theory, there is no need to remove clothing or items from one’s bag or pockets before going through an Evolv smart body scanner, and security staff can screen people at a quick pace.

But Evolv’s own promotional materials indicate that the company’s products frequently issue false alerts, which the company has not disputed. The exact misidentification rate is unknown, as Evolv and its competitors tightly control their data. But a review of company brochures, which Evolv says show figures from a “demonstration account,” and testimony from a prospective customer suggest the scanners may misidentify objects so often that if Evolv’s scanners were installed throughout the New York subway system, hundreds of thousands or millions of riders might be flagged as threats each week.

The systems are also costly. An Evolv subscription costs between $2,000 and $3,000 per scanner per month. Adams has said that he would propose a small-scale pilot program; taking into account the trained staff required to operate each machine, it could cost hundreds of millions of dollars annually should the mayor decide to scale that up to cover each of the 1,928 entrances to New York City’s 472 subway stations.

The Adams administration has assured the public that it’s doing its due diligence in researching the weapons detection technology. “Mayor Adams has made clear that public safety is his top priority, and he is willing to test and analyze numerous forms of technology in a legal, responsible way to protect New Yorkers,” Adams’s press secretary, Fabien Levy, said in a statement to New York Focus and Fast Company.

But the state of the smart body scanning tech raises serious questions. As Patriot One’s Evans noted to IPVM, “weapons detection solutions are still in the early stages of their innovation cycles,” and trying them out in new venues “can be a logistical nightmare.”

False Alerts

Evolv is one of the fastest growing smart body scanner companies, with 84 new customers in 2021, including stadiums, schools, hospitals, and theaters, according to investor materials. The company was founded in 2013 as a spinout of a tech incubator founded by an ex-Microsoft executive, with funding from Microsoft founder Bill Gates, former Florida Governor Jeb Bush, and other investors.

In the wake of the Brooklyn subway shooting, Evolv’s CEO, Peter George, publicly touted his scanners’ ability to distinguish between guns and other items. But evidence, including the company’s own marketing materials, suggests that the technology has trouble with misidentifying everyday objects.

According to the company’s “alert recognition guide,” the systems come with an “alert tagging” feature, so when the scanners ping someone and they are funneled to secondary screening, security workers can log what item the system detected as a weapon. There are tags for “threats,” like guns and knives. Meanwhile, the tags for “benign” objects shed light on some of the items Evolv systems most frequently misidentify as weapons: umbrellas, eyeglass cases, headphones, and laptops.

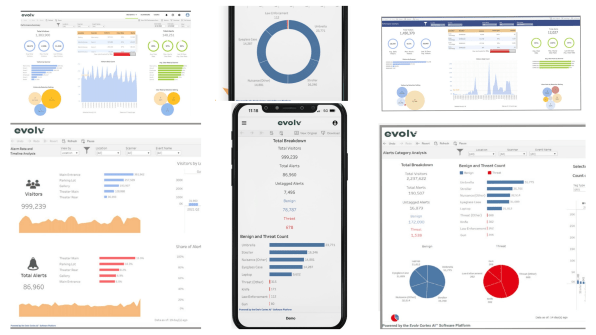

As an Evolv system collects alert tagging data, it displays them in charts and graphs on its “insights” interface, screenshots of which are included in various company brochures. An Evolv spokesperson told New York Focus and Fast Company that the data shown in those screenshots are “fictitious” and taken “from a demonstration account.” But most of the scenarios depicted in the various screenshots paint a similar picture: where around one in 10 people that go through the scanners trigger an alert, and less than 1 percent of those alerts are in fact for confirmed weapons.

In one scenario, a brochure screenshot shows Evolv systems sounding the alarm on nearly 9 percent of a sample of more than 2.2 million people scanned over a three-month period. Of those more than 190,000 alerts, 172,000 were tagged in the scenario as being for benign objects, including nearly 52,000 umbrellas, nearly 36,000 strollers, over 31,000 eyeglass cases, and more than 23,000 laptops. Only 1,538 of the alerts, or about 0.8 percent, involved a confirmed threat — including 206 non-law enforcement guns, which made up 0.1 percent of the alerts in the scenario.

Other brochure screenshots show Evolv systems pinging (again) nearly 9 percent of nearly a million people screened over three months; of those alerts, only (again) 0.8 percent were for confirmed weapons. Other screenshots show systems sounding the alarm on 11 percent of nearly 1.4 million people; again, only 0.8 percent of those alerts were for confirmed weapons. And yet others show systems pinging 10 percent of nearly 235,000 people scanned over a one-month period, with, again, 0.8 percent of alerts for confirmed threats.

Two outlier scenarios show less than 1 percent of people who went through Evolv systems triggering an alert. However, in both scenarios, the screenshots show that the systems’ adjustable sensitivity feature — which has six preset levels — was turned down to the second-lowest setting for most of the session.

New York Focus and Fast Company asked Evolv whether the numbers in the brochure screenshots accurately reflect real-world data from Evolv scanners. The spokesperson replied with the following statement: “Alert rates vary per customer. No conclusions about the Evolv Express system should be inferred from these images, which are used to demonstrate the type of information and analytics the system provides to address the security and event operation needs of our customers.”

The issue of false alerts has also been raised by potential Evolv customers. During a local school board meeting in Urbana, Illinois, in November — first reported by IPVM — a board official complained that, when school staff tested out Evolv’s body scanner system, Chromebook laptops prompted alerts 60 to 70 percent of the time because their hinges were shaped similarly to the barrel of a gun.

An Evolv representative at the meeting responded that the artificial intelligence could eventually learn to distinguish between the laptops and guns if it was taught to. He also pointed to Evolv software’s adjustable sensitivity settings, but warned that turning down the sensitivity to avoid false alerts would create the possibility that the system would miss threat objects.

“There are settings you can put it on to miss the Chromebook, but you’ll also miss certain handguns,” the representative said.

Secret Data, High Cost

In an attempt to better understand Evolv’s strengths and weaknesses, IPVM, the security and surveillance tech research firm, attempted to test and research its products itself. But in December, after three months of back-and-forth, Evolv declined to disclose detailed information or allow the researchers to independently test its products, according to IPVM, citing the need to keep “potential threat actors in the dark about security measures.”

Rather than allowing IPMV a hands-on experience, Evolv has instead touted a report from the University of Southern Mississippi’s National Center for Spectator Sports Safety and Security (NCS4), which showed Evolv beating out Patriot One during field tests. (Patriot One’s field test report showed its system mistaking cell phones, smart watches, and umbrellas for weapons.) But, as IPVM has pointed out, NCS4 has only released a truncated version of the Evolv report, which doesn’t include a breakdown of false alert data, a breakdown of successful threat detections, or the sensitivity settings used during the tests. Evolv has made the full report available only to “qualified security professionals” who enter into a non-disclosure agreement.

When New York Focus and Fast Company asked Evolv about real-world data, the spokesperson responded that “publishing a blueprint of any security screening technology is irresponsible and makes the public less safe.”

“It is well understood that the security community closely guards information related to the specific performance of technology related to threat detection,” the spokesperson said.

New York Focus and Fast Company also reached out to some of Evolv’s current customers in New York City — the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Lincoln Center, the Jacobi Medical Center, and the American Museum of Natural History — to ask about their experience with the body scanners. Citing “museum safety,” the natural history museum declined to answer any questions. The other venues did not respond. Adams’s office also did not respond to questions about the accessibility of performance data.

Amid a list of follow-up questions to Evolv, New York Focus and Fast Company asked how, for its government clients, taxpayers are supposed to understand the pros and cons of the systems their elected officials are considering purchasing. The spokesperson did not respond.

Smart body scanners come with a hefty price tag. Evolv offers a subscription-based model, in which customers pay between $2,000 and $3,000 per month per scanner, which comes with its software and interface. Smaller municipalities have paid that for the technology at public buildings: This year, the city of Detroit entered into a 4-year, $1.3 million contract for 10 Evolv detectors, while a Champaign, Illinois, school district is paying $237,000 a year for eight.

Given the system’s speed and reduced need for security personnel, Evolv claims that this pricing could generate “up to” 70 percent cost savings for venues that would have otherwise installed traditional metal detectors. But the New York City subway system has no other plans for scanners or metal detectors; to install the technology across the whole system, taxpayers might have to shell out hundreds of millions of dollars each year.

Installing an Evolv system at every entrance to the subway could cost between $46 million and $69 million per year in Evolv subscription fees alone, before any bulk discounts. The system would also require workers to monitor the interface and conduct secondary screenings. Evolv did not respond to questions about how many workers it recommends at each body scanner; investor materials suggest as many as six for high-volume situations. Some of these workers would likely need to be armed, since the point is to screen for weapons, so the city or the Metropolitan Transit Authority, the state agency that runs the subway system, would need to hire or assign thousands of police officers or security personnel to attend the stations, almost all of which operate 24 hours a day.

Whatever the cost, it’s important that subway riders aren’t the ones left footing the bill, according to Rachael Fauss, an analyst at Reinvent Albany, a state accountability watchdog. “Riders pay for other upgrades to the subway system through the fare box,” she said. “With the question of who should pay for this, the most important thing to know is, will it have an impact on riders?”

The Adams administration did not respond to questions about where in the subway system weapons detection tech would be installed, how many workers the detectors would require to operate, nor whom the mayor would expect to pay for them. “Of course, any technology that could possibly be utilized in the subways would be coordinated with the governor’s office and the MTA before ever being used,” said Levy, the press secretary.

Do They Make Sense for Subway Stations?

During the Urbana school board meeting, the Evolv representative said that workarounds are often needed to minimize false alerts. In some places, he explained, clients have organized a policy where people quickly pass their laptops around the scanner module before walking through. Other times, particularly in schools, people “catch on” to the system’s idiosyncrasies and make adjustments to limit false alerts.

“They realize, ‘Okay, if I’m going through and I have this giant water bottle that [triggers an alert] every time, I want to keep that at home so I don’t have to go to the secondary screening,’” he said. “The good part is, it’s the same people coming in every day for the most part.”

Such workarounds probably won’t be feasible in a subway station.

Schools and ticketed venues, where smart body scanners are mostly currently deployed, are “controlled environments where people don’t normally go,” said Donald Maye, head of operations at IPVM. As a result, patrons only bring certain items that might be detected by the body scanners to those venues — likely hence Evolv’s alert tagging presets for umbrellas, strollers, and laptops.

But public transit riders — coming to and from home, work, errands, or elsewhere — carry any number of elongated metal items that could get pinged, which could make for long lines at secondary screening.

“If your train is pulling into the station, and you’re waiting behind 20 people to get in, you’re not getting in,” said Lisa Daglian, executive director of the Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA. “We’re looking for riders to get back into the system, not at reasons for them to stay off.”

Speaking to IPVM, Evans of Patriot One offered a “typical” example false alert rate of 5 percent at a more controlled venue. But on the subway, one could see as high as a 30 to 50 percent false alert rate, he estimated. With Covid-era weekday ridership regularly hitting 3 million, that’s hundreds of thousands of people funneled to secondary screening daily.

“You cannot force a very large, highly undirected system like the NYC Subway system to suddenly act in a Directed manner,” he said.

Evans also shared that some weapons detection systems “react very poorly to external interference, such as the vibrations from a train,” which could further add to the false alert rate.

“Maybe it would work on the ferries, and maybe it would work on the commuter rails” where there are fewer customers, speculated Daglian. “But I remain skeptical.”

Neither Evolv nor Patriot One nor their direct competitors currently have public transit subscribers — though some have explored the idea. In 2017, after the detectors malfunctioned during a demonstration, the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transit Authority piloted an old model of Evolv’s scanners in its rail system, which, at around 350,000 riders per weekday at the time, touted roughly one-tenth of the New York City system’s Covid-era weekday ridership. The following year, the LA Metro reportedly considered both Evolv and another competitor, the United Kingdom-based Thruvision Group, but neither bid ever came to fruition, and Evolv seemed to have dropped any immediate ambitions to expand to public transit. (Thruvision did not respond to New York Focus and Fast Company‘s requests for comment.)

In fact, before the Brooklyn subway shooting, Evolv had given almost no public indication that it had subway customers in mind. In its most recent earnings call with investors on March 14, a month before the shooting, executives touted new stadium, school, theater, casino, and other customers, but never mentioned public transit systems, nor any potential customers that would need to screen anywhere close to millions of people a day.

A spokesperson for Patriot One told New York Focus and Fast Company that the company “will be talking with officials at New York City Hall in the coming weeks about how we can work together to make the city safer and keep weapons out of venues.” However, the company currently has no plans to install its systems in the subway, “since there is a lot of analysis to be completed to ensure an effective use of the technology.”

A Surveillance Tech Unicorn

Last year, after introducing an upgraded version of its smart body scanners — which the company says can screen more than 3,600 people per hour, 10 times faster than a traditional metal detector system — Evolv went public. It did so by merging with a special purpose acquisition company, a publicly traded shell corporation set up by investors to merge with or acquire companies that want to avoid the multiple rounds of fundraising, business plan refining, and prolonged scrutiny that accompany the traditional initial public offering process.

The year before going public, Evolv made less than $5 million in revenue, according to investor materials published by the company. But the merger and subsequent fundraising quickly earned Evolv $470 million in investments and a $1.7 billion valuation. Such disparity between earnings and valuation isn’t uncommon in the tech space. But it forces companies to focus on growing as quickly as possible — which can lead to overplaying their technology’s capabilities, according to watchdogs.

“If your business model is heavily dependent on sales and marketing to bring awareness to your product, you want to be as strong and as aggressive as possible,” IPVM’s Maye told New York Focus and Fast Company.

Since rolling out its new model, the company hasn’t brought in as much revenue as it anticipated, which executives attribute to the omicron variant of Covid-19 taking its toll on attendance at ticketed venues. In March 2021, Evolv projected $53 million in revenue for 2022, but reduced that to around $30 million in its latest earnings call. The adjusted revenue projection comes as the company is burning through investor cash: $61 million in 2021, and a projected $95 million for 2022.

Like many public tech companies, Evolv has also recently been hammered in the stock market. Its stock is hovering around a quarter of its initial price, with metrics still showing that it may be overvalued. Its competitors, like Patriot One and Thruvision, are also nowhere near their initial stock prices and burning through investor cash.

These struggles make it important for executives to boost their companies’ financial performance. “Internally, that’s a lot of pressure to get wins — to basically lock in business,” said Maye. And Evolv is now taking an aggressive posture when it comes to selling its systems. It has upped the number of salespeople and executives, both of whom carry sales quotas, according to the latest earnings call, and it has begun selling its systems through more than a dozen larger security and tech “partner” companies.

And that makes it all the more necessary for officials to be forthcoming about the systems they’re considering, according to advocates.

“Rather than parroting marketing claims from questionable startups, city officials should be giving New Yorkers the facts on this technology,” said Cahn of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project.

Adams has been particularly willing to entertain sales pitches from the surveillance tech world. In March, the New York Jewish Week reported that he was considering installing video surveillance drones on rooftops in “higher crime areas,” an idea pitched to him by two drone company CEOs at an NYC–Israel Chamber of Commerce event, and the mayor has talked about expanding the police department’s facial recognition capabilities. Adams has also expressed an eagerness to engage with the speculative tech world in general: He converted his first three paychecks as mayor to cryptocurrency, and exclaimed that he wants New York City “to be the center of cryptocurrency and other financial innovations.”

But tens or hundreds of millions of dollars for tech that might routinely interrupt residents’ daily lives is a different ball game, critics say.

“The MTA has already made investments [in public safety]. Does, say, building off of that — improving the reliability of the cameras — make more sense?” said Fauss, the analyst with Reinvent Albany. “These are the types of questions that taxpayers should be asking. Because someone is going to be paying for this.”

This article was published in partnership with New York Focus, a nonprofit newsroom covering state and local politics in the Empire State. Sign up for their newsletter here.