‘Game Changers’ Reflects on Evolution of Arcade & Home Entertainment

As a kid during the late 1980s, young Jeff Hubbard walked into a Toys R Us one day with his father, who instructed him to pick out whatever he wanted. Hubbard made his way to a big room filled with glass shelves lined with slips of paper colorfully depicting which video games were available. That day, he selected “Top Gun,” a game for the Nintendo Entertainment System based on the 1986 film of the same name, and three or four other titles.

They then brought the corresponding slips to the checkout clerk, who exchanged them for hard copies of their respective video games, the first Hubbard ever owned and played.

“I got into a rush to hook it all up when we got home,” Hubbard, who presently owns and operates Warp Zone Arcade in Brandon, Miss., now says.

Around that time in his life, Hubbard largely played outdoors, although he would occasionally shift gears and play video games, especially during rainy days. One night, however, when he was sitting in his bedroom, Hubbard heard music drifting from his dad’s office across the hall, where his family kept its Nintendo console. Following the sound to its source, Hubbard walked in to find his sister playing “The Legend of Zelda.”

“When I heard the dungeon theme play, I knew I was hooked,” he recalled about how his love for gaming began.

Hubbard still owns his original, gold-colored “The Legend of Zelda” cartridge from his childhood as part of his collection, along with other ’80s classics such as the original “Super Mario Bros.” He decided to open Warp Zone Arcade 11 years ago so that he could share his lifelong passion with people who may not normally be able to experience the classic games of his youth.

“Arcades like mine aren’t around so much any more, and the cabinets I’ve collected took years to find and get ahold of,” Hubbard said. “Figuring out where surviving machines might be is part of the challenge, and a lot of the machines I have I learned of through word-of-mouth. You have to know the right people, since many old places have long-since been shut down or picked clean.”

“There’s also not that many people who still know how to work on them, either,” he added. “Despite all that, I wanted to be able to bring back some of the charms of classic arcades and mix it in with a modern touch, to give people a chance to come and relive the past and forget about their troubles and worries for a while.”

Preserving and Sharing Nostalgia

In addition to offering a space for community members to test out and play video games old and new, Warp Zone Arcade also performs retro-game restoration and cleaning services for games and consoles, holds weekly gaming tournaments and hosts birthday parties.

Hubbard is not alone in his efforts to help preserve and share the nostalgia of classic video games. The Mississippi Museum of Natural Science is currently hosting a traveling exhibition titled “Game Changers,” which aims to allow guests to discover how innovation has shaped the video-game industry from its origins into the present.

The Canada Science and Technology Museum developed and produced the exhibit, which Science North manages in partnership with the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and video game manufacturer Electronic Arts. “Game Changers,” which debuted in Ontario, Canada, in October 2016, touches on gaming history from the early days of “Pong” analogues to modern games, as well as what the industry may look like in the future.

“Kids will get to engage with games they may have never seen before, while parents might be jazzed to see some classic things on display from their era,” Thomas Joseph Tippit, visitor services manager at the Mississippi Museum of Natural Science, said.

“I expect people will be able to come away with a deeper appreciation for video games that are outside their own experiences, whether that be games that were popular in arcades during the ’80s or any of the places the industry has gone since then. I think it’ll be plain to see how far we’ve come from the modest beginnings of things like ‘Tennis for Two.’”

From ‘Tennis for Two’ to ‘Pong’ and Beyond

Physicist William Higinbotham, who had served as the head of the electronics division of the Manhattan Project to develop an atomic weapon from 1943 to 1945, developed one of the earliest prototypes for video games, “Tennis for Two,” in 1958 as part of a display at an annual exhibition at the Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York.

After learning that the Donner Model 30 analog computer at Brookhaven could calculate ballistic missile trajectories or a bouncing ball with wind resistance, Higinbotham decided to create an interactive demonstration for guests at the exhibition in which players could turn a knob on a cathode ray screen to adjust the angle of the ball and push a button to hit the ball toward the other player. The game, which Higinbotham allegedly created in only a few hours, proved to be a success.

As Higinbotham worked at a government lab, he never patented the device, which eventually faded from memory. Sanders Associates received the first patent for a video game in 1964, which the Magnavox company then bought and used to begin producing video-game systems in the 1970s.

Though Higinbotham eventually testified about his invention as part of a lawsuit from competitors wanting to break the Magnavox patent, those involved ultimately settled the case out of court. Video game manufacturer Atari eventually went on to create the version of the game most people are likely more familiar with, “Pong,” in 1972 as one of the earliest arcade games.

“The kinds of old ARPANET computers that United States government facilities used back then, the kind ‘Tennis for Two’ would have used, probably wouldn’t even be able to run something as simple as a phone game like ‘Snake’ now,” Tippet said.

“They also needed huge computers back then for even the simplest things, but now you have advanced simulators that can run on hardware that’s so much smaller, and the possibilities are so much greater. It’s honestly a privilege to be able to experience the kinds of things that manufacturers can construct now.”

A Walkthrough of ‘Game Changers’

The “Game Changers” exhibit at the Mississippi Museum of Natural Science displays roughly 120 influential video games, 16 of which visitors can test out for themselves on consoles throughout the exhibit, including classics like “Pac-Man,” “Tetris,” Super Mario Bros.” and “Space Invaders.”

The exhibit also explains the technology behind video-game graphics throughout history, including a station where visitors can explore the pixel-art technology early games used, learn how developers created characters and other assets with it, and even create pixel art of their own. Other displays cover 3D rendering and motion-capture technology used in modern games, including a real motion-capture suit that actors wear to record advanced animations.

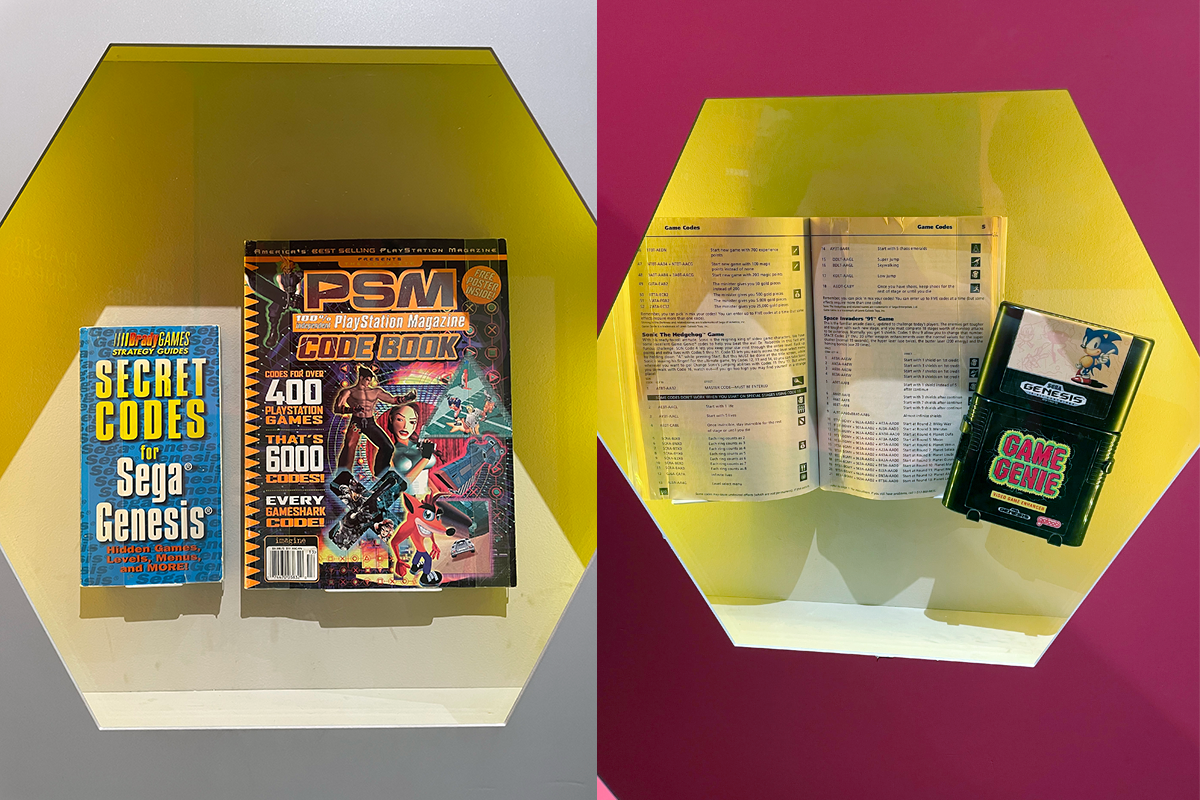

“Game Changers” also contains displays of video-game peripherals, including giant replicas of a Nintendo Entertainment System controller and a GameBoy, to give guests a more detailed look at their construction. Visitors can play “Super Mario Bros.” and “Tetris” on those two systems, respectively. Other items include a 6-axis gyroscope, an XBox Kinect and code peripherals such as the Game Genie.

“The first time I ever held an old Atari controller was when I was a kid, and my neighbor let me play with one after I did yard work for her instead of (receiving) the usual juice or cookies,” Hubbard said. “That was one of the earliest home controllers, and you had one joystick and one button. You could move and either jump or shoot depending on what you were playing.”

“Then we moved on to the first Nintendo console, and suddenly you had two buttons and could do way more,” he continued. “Then the Super Nintendo came along, and we had six buttons, and then controllers started becoming wireless. I’ve acclimated to all of them over the years and some, like the old Nintendo 64 or Dreamcast controllers, might be hard to go back and try to use now, while others, like Playstation controllers, haven’t really changed that much over the years. At the end of the day, comfort is king when it comes to controllers.”

Early video-game magazines like Nintendo Power and GamePro offered guides and cheats that players could use to gain an advantage during gameplay. This trend led to the creation of hacking engines such as the Game Genie. Hacking thus became an important element of gaming culture, the exhibit explained.

“Those old-school games were hard, and people were always looking for a way to get a leg up and find an advantage, like extra lives or continues,” Hubbard said. “Just about any ’80s kid probably still remembers the Konami Code for ‘Contra’ and other games. Codes and hacking go hand-in-hand with things like the Game Genie, while the modding scene for things like PC games revolves around people trying to find ways to put whatever strange things they can imagine into a game.”

One display covers how sound design became a core component in helping games reach critical and commercial success. An interactive quiz challenges visitors to identify music and sound effects from different games, such as “Mega Man” and “The Legend of Zelda.”

“Those classic tunes will inevitably get stuck in your head, and that’s an integral part of the experience,” Hubbard said. “It just invokes great nostalgic memories in people. We’ve come a long way from 8-bit soundtracks up to CD-quality sound and beyond with game tracks becoming more orchestrated, but to this day if I hear a sound effect like the ring-collecting sound from ‘Sonic the Hedgehog’ come out of somebody’s phone, I instantly recognize it because I played those games like crazy. Music and sound in games is part of the evolution, and key to setting the mood for whatever a developer is going for.”

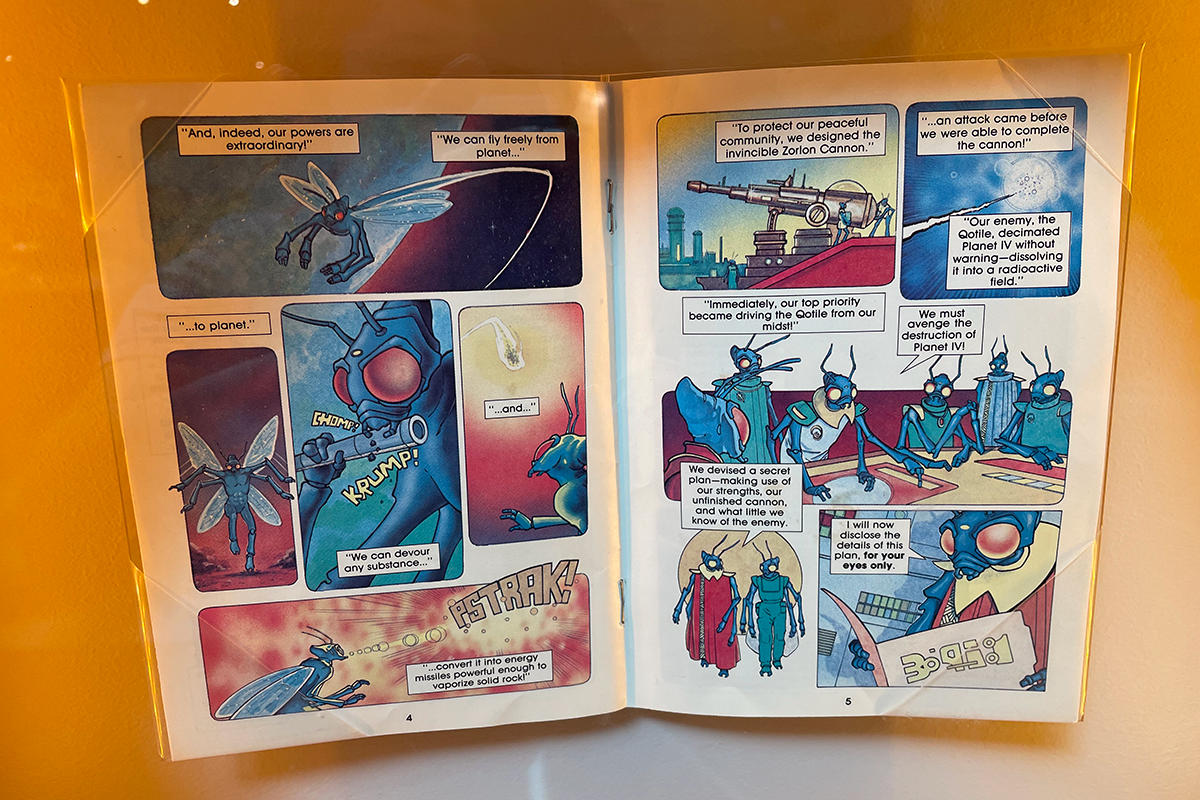

Other parts of the exhibit cover the evolution of story and narrative in video games, from the more rudimentary or even absent stories common in the earliest games to the more choice-based narratives that have become common in recent years.

“Game Changers” explores the intersection of audio, graphics and gameplay during development, as well as setting, character design and what developers face in some choices as basic as deciding the location a game will depict.

“Hardware limitations were the key factor in the development of story in games,” Hubbard said. “Developers were definitely limited in what they could do in the early days, and while story was still important, it wasn’t critical back then.”

“Games like ‘Mario’ did great even with a minimalist story, but then as the hardware evolved and more and more things became possible, we started moving into the age of role-playing games like ‘Dragon Quest,’ ‘Final Fantasy’ and later games like ‘Chrono Trigger,’” he added. “Now, games are becoming more and more like movies, while some will give you a basic story and then let you be free to go out into the open game world and figure out what you want to do on your own.”

‘Symbols of Joy’: Gaming’s Past, Present and Future

In addition to showcasing video games of the past and the industry’s evolution, “Game Changers” aims to explore ideas regarding what might be possible for the future of gaming technology. One display explains the science behind augmented-reality technology, as is used in games such as “Pokemon GO,” including a camera that projects digital graphics onto people to make them look like a video-game character.

The exhibit also identifies current gyroscopic technology used in modern controllers and what may go into controllers of the future, as well as stations allowing visitors to try out virtual-reality technology for games, which is increasingly making headway through devices such as the Oculus and Valve’s Index VR headset.

“Games today have become something akin to major events like summer blockbusters,” Hubbard said. “As the industry pours more and more resources into games as entertainment, the landscape is constantly changing, and it’s tough to nail down what it might look like years from now.”

“The push for VR is getting stronger, and while it still hasn’t caught on in a widespread way just yet, we might get to the point where VR in every home is both possible and affordable,” Hubbard suggested. “When you look at what’s possible now on consoles like the PlayStation 5, I can also see evergrowing realism becoming possible as games become more film-like.”

Guests who visit the museum can also spot original concept art, storyboards, level-design plans and scripts from numerous games, as well as installations where experts from the industry like Mac Walters of Bioware and Maxine Durand of Ubisoft describe how they develop games.

“At the end of the day it’s the nostalgia factor that brings people back to these classic games,” Hubbard said. “Everyone has their first game and their first system, whether it was a Sega Genesis, a Nintendo 64 or the original PlayStation. There’s just something about a well-made game, no matter when it came out, that creates an experience nothing can beat.”

“A lot of older titles were challenging, and there’s a sense of reward and accomplishment that comes from playing them,” he added.

“For me, though, what makes a game timeless is the memories you hold onto. It doesn’t matter if you were a Sega person or a Nintendo fan, everyone has that special game that means so much to them, whether it was because they shared it with their family, it got them through a tough time in their life or it was just made really well. They serve as symbols of joy in our lives, and that’s what makes them timeless.”

“Game Changers” will remain on display at the Mississippi Museum of Natural Science through Sunday, April 24. General admission to the museum is $8 for adults, $6 for youths ages 3 through 17, $7 for visitors who are 60 years old or older, and free for children under 3 years old. For more information on the museum and its exhibits, call 601-576-6000 or visit mdwfp.com. To learn more about Warp Zone Arcade (393 Crossgates Blvd., Suite C, Brandon), call 601-706-4764 or find the business on social media.